You should not keep any animal except a cat… Anyone who wishes may sleep in leggings… They should not snack between meals.

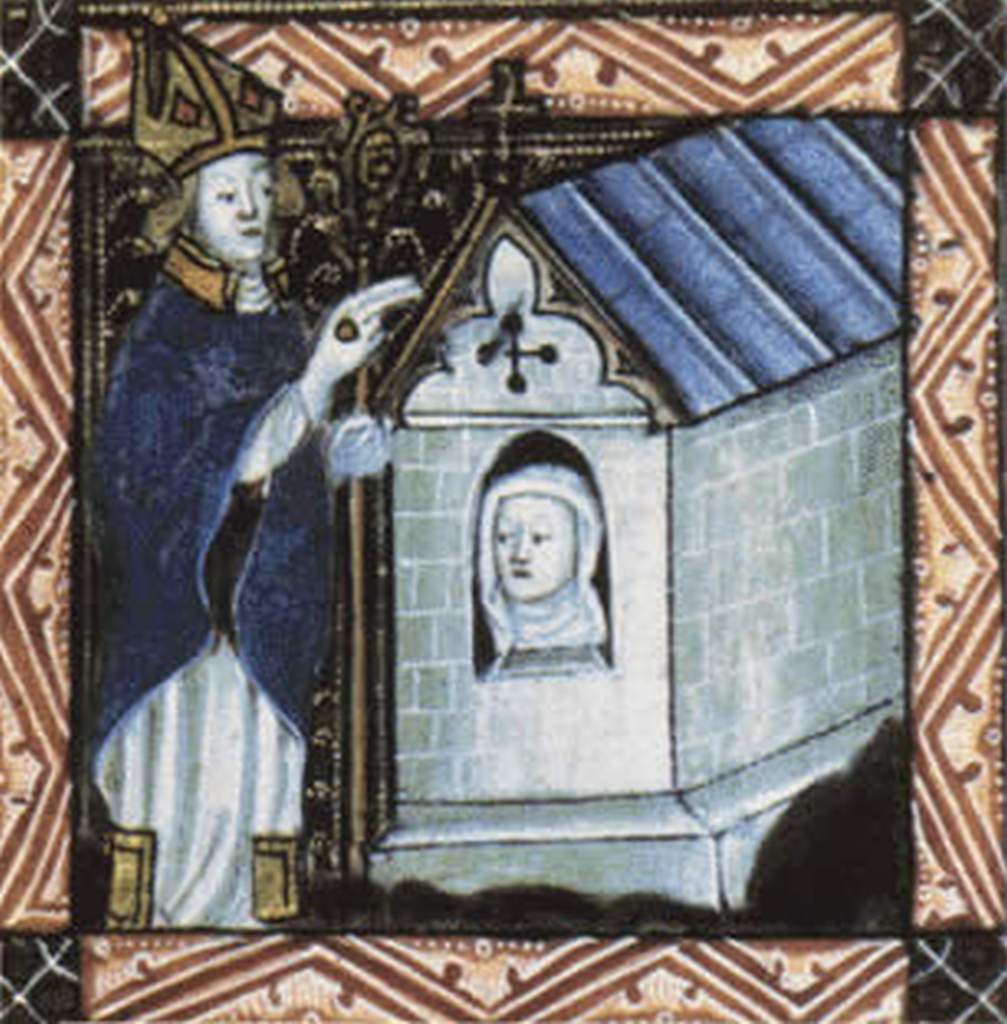

These are a few of the more specific instructions given in the medieval treatise for religious recluses now known as Ancrene Wisse, ‘A Guide for Anchorites’, which was the focus of my master’s dissertation.

These rules offer a fascinating and often charming insight into a very alien way of life, but my particular focus is on the Guide’s highly detailed instructions on prayer. Anchorites, who enclosed themselves in cells to lead lives of prayer and contemplation, followed the Hours (the prayers offered by monastic orders at seven fixed times daily) and a sprawling structure of other prayers to God and the saints. The Guide instructs them on the proper posture, words, and alignment of heart for this daily work, and their intercession before God is seen as uniquely powerful, a heroic act of devotion and an ‘anchor’ to the Church.

This is the spirituality and way of life which I plan to spend the next three years studying – but if I’m honest, this is also where I get impostor syndrome. More often than not, my academic work on the value of prayer for these medieval people throws my own prayer life into uncomfortable relief. I often struggle to pray at all, let alone commit my whole life to it. I am used to thinking and writing theoretically about the power of prayer, but in practice, I find this difficult to believe, at least to the extent that it becomes a discipline in my life.

This isn’t a practical problem, exactly: plenty of academics study religion without any faith of their own. My writing about medieval anchorites and their connection to the Divine doesn’t need to be matched by a living connection of my own in order to fit into the literary academy’s way of doing things.

And it’s not as if I would want to emulate the exact kind of prayer life which the Guide recommends – I’m a modern, Protestant evangelical living in a world which is almost unimaginably different from the high Middle Ages, so praying to the saints and mortifying the flesh as a means to more effective prayer are not concepts which really register.

But my literary interests aren’t arbitrary. I find anchorites, medieval liturgy, and models of prayer interesting precisely because of my faith, and the mismatch between the spiritual and academic spheres of my life feels more acute because of this basic connection. Maybe you’ve felt the same thing: your faith is supposedly a part of your work, and you know that faith and scholarship can and should be integrated, but this ideal is the exact point at which your own inadequacy is most pressing.

For me, the crucial question is how I can write with integrity about the transcendent, unifying power of prayer in these medieval texts, while being honest about the limitations on all human efforts to pray – especially my own. I often think of the anchorite’s lifestyle as obedience to the Biblical command to ‘pray continually’, and this is perhaps a place to start: even the recluse’s extreme devotion does not involve literally continual prayer, but their life as a whole is seen as an act of intercession and worship.

It’s impossible to know for sure how medieval anchorites themselves felt about their lives, but I imagine they must have felt the gap between the high calling of their life and their own human capabilities, and I hope that they were able to balance this with the mercy of God. This is something that academics need to be able to do too: to resist the combination of perfectionism and fear (which can come from both church culture and academia), knowing that we don’t need to add up our good works to a sufficient whole, but instead receive overflowing grace from the only true Person of integrity. Only this grace allows us to live a life of true worship.

Alicia Smith recently completed her MPhil and is about to begin doctoral studies in English literature at Oxford University, at Queen’s College. She is originally from Leeds.

- Vision and revision: listening to T.S. Eliot - August 19, 2024

- A Reformational perspective on manuscript studies? - March 26, 2024

- ‘Men of ability’ and the incarnate Christ - January 29, 2024