‘Calling’ or ‘vocation’ is something we mention fairly often at Faith in Scholarship. In modern English it’s mostly used, in both secular and church contexts, to refer to profession: often to a certain kind of demanding, valued profession, such as medicine or pastoral work. Many Christian thinkers have (rightly) reclaimed this kind of value for all kinds of work, pointing out that God can be glorified in anything from retail to programming to construction to academia.

Calling in the Bible

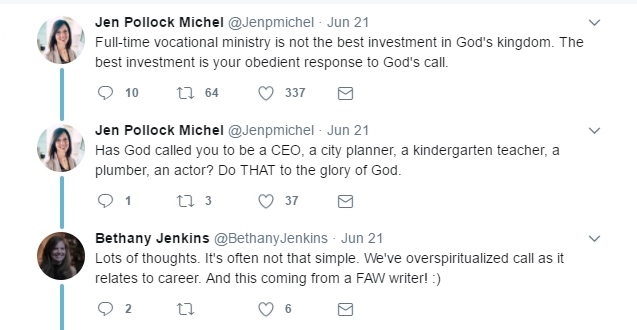

But is ‘calling’ the right way to talk about the value of work? I recently noticed an interaction on Twitter between two Christian writers whose work I love – Jen Pollock Michel, author of the excellent Teach Us To Want, and Bethany Jenkins, who runs the Gospel Coalition’s ‘Every Square Inch’ initiative on faith and work:

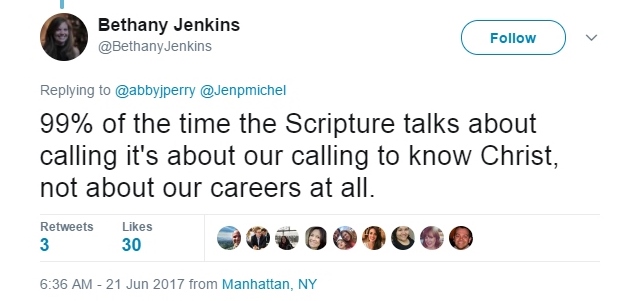

Michel’s initial tweets had me nodding and agreeing – but Jenkins’ corrective fit with some reading I’ve been doing recently as part of a group here in Oxford (‘Christians in Academia’, a programme run by the Oxford Character Project). Ahead of our discussions about ‘vocation’, we read the first chapter of a book by Gary Badcock, The Way of Life, in which he pointed out much the same as Jenkin’s second tweet above. The call of God in the Bible is almost never connected directly to profession or work as such. Instead, we’re called to repentance (Mark 2:17), salvation (1 Cor 1:2), and holiness (2 Tim 1:8-9).

Work and identity

None of this is to say that the ideas behind ‘faith and work’ thinking are wrong! The value and holiness of work done well for God, using our given gifts and circumstances, is undeniable. But we can unintentionally, and unbiblically, narrow our thinking by linking vocation – the call of God – too closely with our work or role in society (paid or not).

God calls us as whole people, in every part of our lives. This is something I’ve been taught ever since I can remember. But it’s dangerously easy to use the idea of God’s calling to make the label of ‘academic’ (or teacher, or researcher, or scholar) into my central identity. First and foremost, God has called me to be his child, his disciple.

Maybe it’s better to talk about profession and calling using verbs, not nouns. I am called to love God: in my professional context right now, I do this by reading, thinking, analysing, teaching. In the future those particular ways of loving God may be different, but my calling will be the same. This mindset guards against the potential to spiritualise over-reliance on professional achievements or labels.

What do you think? In what ways is the language of ‘calling’ as regards our work helpful, or unhelpful?

- Vision and revision: listening to T.S. Eliot - August 19, 2024

- A Reformational perspective on manuscript studies? - March 26, 2024

- ‘Men of ability’ and the incarnate Christ - January 29, 2024