“Of making many books there is no end…”

Ecclesiastes 12:12

There is a point of view from which it looks implausible that research in any field could continue indefinitely, century after century, endlessly discovering new things about reality. Part of the classic fin de siècle phenomenon was the suggestion that there might not be much left to discover. But at least since Augustine[1], many Christians seem to have imagined that cultural development will be terminated (or even destroyed) on the Last Day when Christ returns – as suggested by the term ‘consummation’. But this isn’t necessarily a biblical perspective. Christ’s kingdom will never end (Luke 1:33), and there’s a case to be made that cultural development, finally freed from sin, will continue forever under His reign. Might not the created order, once more fully disclosed in the New Creation, be worthy of ongoing scholarly research into eternity?

Be that as it may, there seems to be no slowing down in the rate of scientific progress at present. And what we believe about the potential for ongoing research may affect how we approach our scholarship from day to day. So, continuing our scholarly skills series, I want to share some thoughts on how to find original questions and fresh perspectives on a topic. These were originally prompted by the simple challenge of asking good questions after a talk, but they also apply to thinking up new research projects for ourselves – or our students, if we’re at that stage.

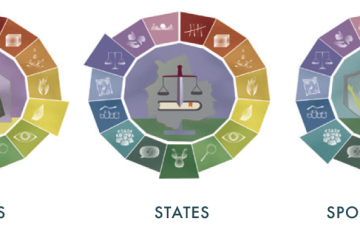

What tips, then, can I offer? My principal advice is actually rather demanding. It is no understatement to say that the created order is inconceivably complicated, and any research programme must sooner or later open up completely unanticipated ideas. Insightful questions, therefore, must come from some framework that provides context and helps locate contours of meaning within the overall coherence of the created order. And such a framework is offered by the series of modal aspects of Reformational philosophy. It’s often from the categories and relationships of this grand model that I find an angle for asking questions on other people’s research, and have found some of the kernels of my own research ideas.

A few specific tactics might also help:

- Look out for reductionism. This is actually the simplest outworking of my advice above.

- Look at motives. Why might this person or group want to study this topic, and why might it have been funded? Why do you like the subjects you do, and why might peer reviewers and funders like your area (or not)?

- Ask “so what?” questions. Academics often give rather little concrete context for their ideas – perhaps because our culture prizes scientific abstraction so highly. But Christian scholars should be interested in the particular as well as the abstract.

- Ask what tenets are best established or most likely to be superseded. The historical dimension of knowledge is likewise often sidelined – as if today’s pronouncements will be subject to no further revision.

In all this, let’s seek a gracious affirmation of the hard work that has gone before – as advocated by Andrew Basden’s Affirm-Critique-Enrich approach and its extension, LACE. And let’s pray that the way we work to answer research questions will be worthy of the age to come, a fitting tribute to Christ the king.

[1] according to Richard Middleton in A New Heaven and a New Earth: Reclaiming Biblical Eschatology (Baker Academic, 2014): p 291ff

(Photo under a Creative Commons Zero public domain licence, via Dreamstime.com)

- Imaging our Creator; imaging ourselves? - February 4, 2026

- Wise Men Still Seek Him - January 6, 2026

- Philosophy in full colour - October 21, 2025