This year, I’ve been doing my research at a noted respository of medieval manuscripts – the Parker Library at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. This location has affected my research practice in lots of ways.

While I was in Canada last year, I relied completely on digitised or photographed manuscripts, as the witnesses to the text I was working on were scattered around various European archives. This year, things are very different: I am spending lots of in-person time with medieval books, one in particular. I’ve taught classes with these artefacts on the table in front of us (the beautiful Peterborough Psalter was a favourite), and learnt lots about how they can help us engage with the medieval past. I’ve had to think more seriously than I had before about what an archive is for, what librarians’ responsibilities and priorities are, and the complicated history of how medieval books and other artefacts ended up where they are today.

I’ve been wondering recently what a Reformational perspective on manuscript studies might look like. I’m far from the most material-oriented manuscript scholar – I’m not doing spectrometric analysis of parchment or thinking overmuch about ink composition. But the material book has become much more pressing to my research than it usually was in my doctoral project. And that seems ripe for the kind of holistic, wraparound analysis that a Reformational perspective offers.

Let me unpack that a little. The reason I got interested in this manuscript was a very small section of it – an account of the conversion of Thais, an early Christian saint whose story I am researching. It’s about 70 words, maybe 4 lines of text, in a book with 246 pages, made up of 4 different volumes bound together and covering a range of centuries and genres in what it contains. If I quoted this section in a survey of the way medieval writers wrote about Thais, I wouldn’t necessarily mention any of the rest of the book – but that would obscure its context and shut down a lot of what a medieval manuscript can tell us.

That’s why it’s become an increasingly popular approach in medieval studies to take a ‘whole book’ approach (as was the theme of a conference I presented at recently) – to place at the centre the fact that any medieval text comes down to us only through medieval books, and those books rarely contain one text only, so each text should be understood in light of its neighbours. What’s more, the physical book itself – how it was made, what uses it was put to, who owned it, how it changed – also affects what we know about the texts within it. All of these aspects are interrelated.

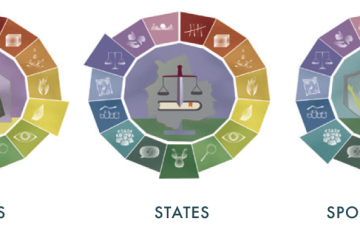

So would, for example, a Dooyeweerdian aspect analysis help schematise some of the ways a manuscript functions in the world, to shed light on this holistic quality which manuscript scholars are looking for? You can find a useful explanation in this older post by Richard of the fifteen aspects which the philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd posited as the fundamental, interrelated ways everything exists meaningfully in the world. I’ve started pulling together ideas on how the study of a medieval manuscript could be illuminated through this framework. I would value suggestions!

Here are some ways these aspects connect:

- The economic role of a manuscript has to be considered in light of the physical – the cost of the materials and their construction into a useable form – but also the aesthetic and sensory – how much of a luxury item is this book, and how do the materials used in its production communicate that through the senses?

- A manuscript is itself a historical record – created at certain points in time, sometimes all at once but usually over a period, whether long or short; the physical and aesthetic elements enable us to identify the different historical stages in its life (sometimes also the biotic elements of interaction with pests and human use)

- A manuscript acts as a central node in a web of interpersonal social relationships, whether in-person or more mediated – patron and book-maker or scribe, writer and reader, writer and annotator, and so on; this extends over time to be part of the historical dimension of the book, via annotation, addition or excision of material, rebinding, digitisation…

- The aesthetic and sensory dimensions of a manuscript affect how much attention is paid to it by scholars and others, contributing to its symbolic value and its modern economic or social potential: e.g., an illuminated manuscript is much more likely to be studied and images of it reproduced for other uses

- Many medieval manuscripts contain religious material, where certitudinal and ethical aspects overlap: doctrine and devotional practice are communicated, while the act of composing or copying itself functions as an act of love for those who will read – and vice versa, as can be seen in many cases when the scribe concludes a text by requesting the reader’s prayer for him.

One way this kind of interwoven attention has functioned in my work on MS 385 is the importance of annotation in working out when the four distinct volumes were brought together into the present composite book. The book is page-numbered with a red crayon, distinct from the ordinary ink of any of the main writing; that physical aspect needs to be brought together with historical awareness that this crayon is seen often through the Parker Library collection and is known to have been used by its original collector, sixteenth-century Archbishop of Canterbury Matthew Parker, and his assistants. So the binding together of the four volumes can’t have been after his day.

This historical aspect becomes more complex when we consider the contents list, also apparently from Parker’s time. It lists several, though not all, of the texts contained in the composite book, including the series of exempla (short edifying stories) where my Thais story is found. It calls this section ‘Some worthless stories’, probably because they represented a religious outlook no longer acceptable to Parker as Elizabeth I’s Reformed archbishop. Here a value judgment has been made according to the certitudinal or pistic (faith-related) aspect in which this section of the book exists – but now in the 21st century, my perspective and purpose in reading these stories is very different, though no less implicated in matters of belief, history, social connection between people, and so on.

I hope to go on to think more about and refine this rough table: your suggestions, or connections to how this perspective might inform your own work, are very welcome!

- Vision and revision: listening to T.S. Eliot - August 19, 2024

- A Reformational perspective on manuscript studies? - March 26, 2024

- ‘Men of ability’ and the incarnate Christ - January 29, 2024