Picking up my series on Christian philosophy in diagrams, I want to share an idea that really excites me at the moment – inspired by Andree Troost’s “What is Reformational Philosophy?”, which I’ve just finished reading. Perhaps not everyone finds diagrams as wonderful as I do, but they have a great ability to present complex ideas all at once, in the simultaneity of a page or screen.

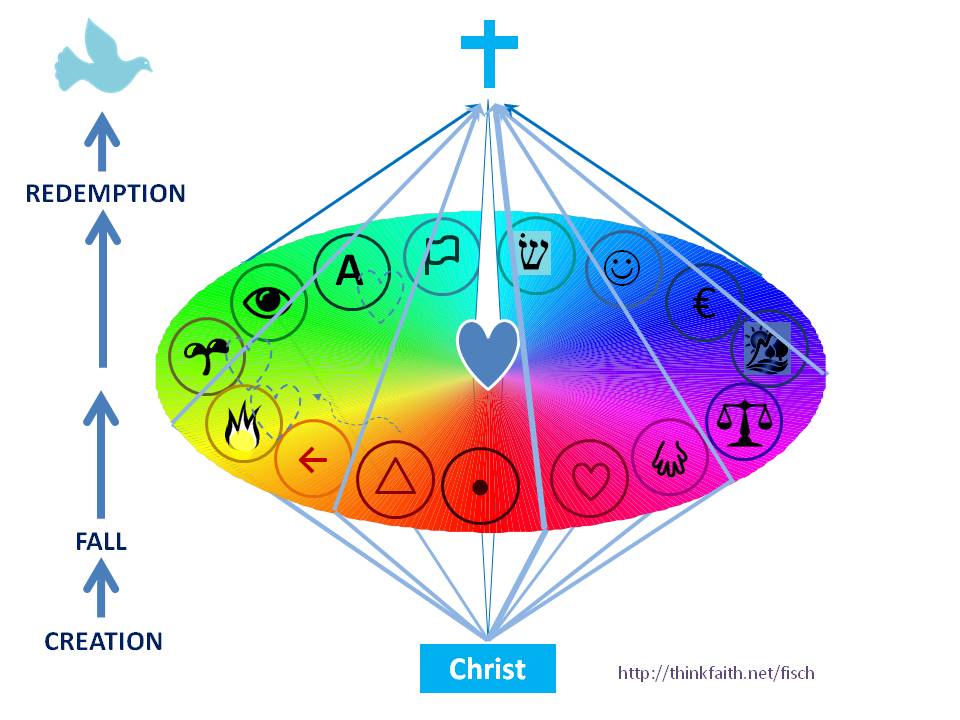

This graphic represents the whole created world as having both immanent (horizontal) and transcendent (vertical) dimensions. It looks a bit like one of those spinning colour wheels you can make by pushing a pencil through a disc, and indeed that’s not a bad model for this big idea of what the world is like. The horizontal disc represents the whole universe of our day-to-day experience, with all the rich, scintillating diversity of temporal things and relationships that we know. This is the reality that everyone experiences in ways we can broadly agree upon: human society and institutions, people, animals, plants and inanimate things, all functioning in many different ways (represented by the 15 symbols around the circumference). At the centre of the disc lies a heart symbol, because this is a model of how we humans experience and influence the cosmos as we look out on it. That much describes the immanent dimension of reality.

The human heart is also at the central point in this disc because the Bible reveals that humans are created as the image of God: the creatures that should image God to the rest of the creation (Genesis 1), and with whose obedience or disobedience the fate of the whole creation is tied up (Genesis 3; Romans 8:19). And Scripture uses “heart” as a metaphor for our religious centre: the concentration point of our conscience and our will, which directs our worship either to God or after an idol. Here, of course, we’re moving beyond immanence perceptions to revealed truth about transcendent reality – which is represented by the vertical dimension of the diagram. This dimension represents what might be called cosmic time or a religious metanarrative: the all-embracing story of the cosmos from creation by God through the Fall in Adam to redemption in Christ Jesus, led by God’s life-giving Spirit. This is a bigger view of time than merely clock time, stretching from the primordial creation, the religious origin in Christ, to creation’s eternal destination, which is for Christ (think of Colossians 1:16). And our heart in a religious sense participates in this “depth dimension” of the cosmos: we transcend our own lifespan by yearning to participate in God’s eternal purposes and to be granted eternal life at the Resurrection (as Paul does in Philippians 3:11).

The diagram above is based on Herman Dooyeweerd’s model of reality. Here, every philosophical view presupposes some religious notion of reality, typically including an idea of where reality comes from (its origin), what holds it together (its coherence) and what it means (its destination). A philosophy in turn provides the framework for more specific kinds of scholarship, such as the sciences, to look at the diversity of reality. The model illustrated here posits the immanent realm as the common experience for such scientific study, while at the same time showing why the transcendent “religious depth dimension” is so important. That is, we cannot locate the centre of reality without God’s revelation of its unity of origin and destination – which is Christ, the revelation of God as both transcendent and immanent. Without that special revelation, the human heart is inevitably drawn towards seeking explanatory unity in one or other aspect of created diversity – which leads to idolatry. This is what Dooyeweerd means by “secularisation”, and the dotted hearts in the diagram here represent some important idolatries of this kind that have shaped Western culture. But this is a topic for a future post.

- Flowers not flavours in AI: How large language models resonate with the beauty of creation - May 19, 2025

- Artificial thinking? - April 2, 2025

- A degree of critical thinking - September 2, 2024