The European Reformation of the 16th century clarified the distinction between Christianity and the Church. The believer’s primary allegiance, claimed the Protestants, was to Jesus Christ, and church congregations were an essential expression of this rather than providing salvation itself. At this time came a renewed emphasis on Christ’s lordship over every area of life: all kinds of work were to be seen as vocations to pursue in service of Christ the coming King.

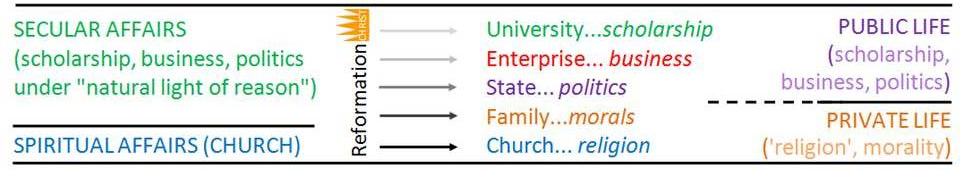

The political legacy of the Reformation included a separation of church and state in both Protestant and Catholic cultures: God called His people to participate in politics as Christian citizens rather than by bringing states under the sway of the church. However, this separation was increasingly misinterpreted as excluding religious motivations from politics. How did this happen? One answer is that, while churches themselves pursued reformed (and counter-reformation) agendas, Christians failed to pursue their work as vocation – so that, within society at large, Christianity continued to be seen under the umbrella of the church. This problem was to prove serious not only for politics.

Arguably the most calamitous point at which the reforming vision was lost was in education and scholarship. Under medieval Scholasticism, man’s natural light of reason was supposed to be fully able, for unbeliever as for believer, to understand and interpret the order of Nature. Christian (i.e. Church) intervention was needed concerning matters of grace: doctrine, ethics, church affairs, while theology, as queen of the sciences, might examine theories of natural philosophy to point out anomalies with regard to Christian revelation. But this dualistic worldview denied a foundational role for faith in scholarship. Autonomous reason could be left to its own devices, it was thought.

Faith in Scholarship?

Some of the Reformers did envisage the reformation of scholarship. Calvin’s concern for this is revealed in his Institutes, even while he is most remembered for political reforms. But within the universities, the strongest proponents of the Reformation remained committed to the scholastic framework for philosophy. And so the project of Christian scholarship was forlorn. The challenge of how to think christianly about the whole cosmos as the creation of God, under the cloud of the Fall, and in the light of its redemption by Christ, was at best an undercurrent.

In the 19th century, a key pioneer of reformational thinking for the whole of life came in the Dutchman Abraham Kuyper. Kuyper argued powerfully for the adoption of a comprehensive reformational worldview by Christians – one that would embrace the diversity and complexity of the whole created order and bear fruit in politics, family life, business, the arts – and scholarship. He was followed in this project by the deeply original Christian scholars Herman Dooyeweerd and Dirk Vollenhoven, whose “reformational philosophy” framework enquires about the origin, coherence and diversity of the cosmos and the many kinds of laws that seem to structure it.

We call this tradition “reformational” to emphasise its open-endedness: reformation must be ongoing, and no creed, policy or theory is perfect. Indeed, we surely never will have perfection, for what can the return of Christ mean but deeper opening up of the created order for understanding by His people, with the obfuscations of sin removed? What is certain is that Christ’s lordship can ultimately leave no part of human life untouched, and we must work hard to discover what this means in our own callings.

Some spheres more reformed than others: While church structures were opened up to the priesthood of all believers, scholarship remained largely unreached by a vision of Christ’s total lordship. Did the reformation project collapse prematurely into the “public/private” divide we now live with?

- Imaging our Creator; imaging ourselves? - February 4, 2026

- Wise Men Still Seek Him - January 6, 2026

- Philosophy in full colour - October 21, 2025