Guest blogger Audrey Southgate reflects on lessons drawn from studying a morally problematic figure.

Some view the past as a shackle from which the present must free itself. By contrast, I grew up delighted by the stories that linked the present with the past. At church, at home, and at school, stories of admirable figures from history served as a source of inspiration. There was no question that we had much to learn from the subjects of these stories, whether Christian martyrs, great-grandparents, inventors, or other heroes. Surrounded by such stories, I came to look to authors from the past for timeless insights that would clarify my perspective in the present.

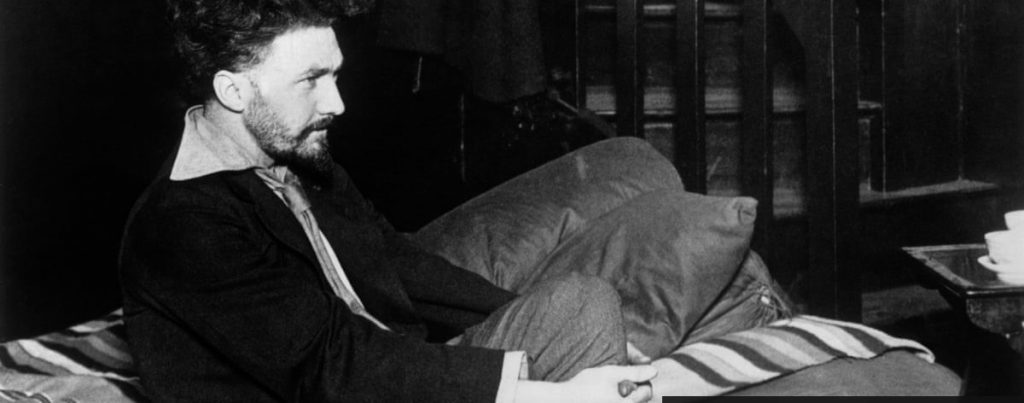

This became somewhat more difficult, however, when I found myself writing my undergraduate dissertation on Ezra Pound. Far from an exemplary figure, Pound is perhaps as infamous for the anti-Semitic slander and fascist sympathies he endorsed in broadcasts during World War II as he is famous for his contributions to modernism in poetry. Like his public views, Pound’s private life was hardly something a Christian would want to emulate: he kept a mistress for most of his marriage and even lived in a ménage à trois for a couple of years. Moreover, his publications and personal correspondence display an arrogance that is corroborated by the recollections of those who knew him throughout his life.

Since I could not admire Pound in several important respects, could I learn anything from him? I had chosen the project because I wanted to learn from how this key modernist had engaged with tradition and ‘made it new’ in his own time. But his appreciation for the poetic heritage was accompanied by scorn for those who didn’t share it or appreciate it as he did. More troubling still, it was accompanied by adherence to one of the most vicious ideologies of the twentieth century. If looking to the past involved the evils Pound espoused, I could not learn from Pound – nor did I expect to learn from the past at all.

In the process, I realized that my expectations were inconsistent with my faith. If I believed that all are fallen, I should not be surprised to find serious faults in any person’s thinking and life. If I believed that God is the author of truth, I should strive to recognize his truths wherever they appear. And if I believed that God showers the earth with common grace, I should expect his truths to appear even in the mouths of faulty people. Rather than asking whether I could learn from Pound, I needed to ask what truths I could learn from Pound, and what faults I could learn to avoid from his example.

As it happens, I discovered Pound does have much to offer. Not only is he a representative of an era whose effects we still feel today; he also models a search for the meaning that transcends particular eras. Comparing art to a river, he described artists as concerned, not with the features of its banks at certain points, but with its ‘quality of motion’, or ‘that which flows’. Pound’s own overarching concern, expressed here, was with the essence of art that transcends the historical and geographical circumstances defining its reception.

Here and elsewhere, Pound suggests his utter commitment to the transcendent – but confines the transcendent to the human artistic tradition. Perhaps the widely-deplored problem with Pound lay, not in his appreciation of the past, nor in his appreciation of this artistic tradition across history, but in what he failed to appreciate from revealed history. He failed to see the source of beauty who transcends all history, and who gives meaning to it: the transcendent God who is also immanent, the Word who became flesh and came to dwell among us. And because of this, Pound failed, too, to practice the virtues of faith, hope, and above all love for God and man which are beautiful in all ages.

Pound thus serves as a warning not to let our appreciation of human traditions keep us from loving God or other people. At the same time, Pound serves as an encouragement to dedicate ourselves to pursuing what is truly timeless. In a way, the very magnitude of his failures makes him all the better as an example of the importance of seeking the Truth – and as an example of the importance of discerning the timeless truths a person expressed from the failings that invariably accompany these insights.

Audrey Southgate is working towards a DPhil at Merton College, University of Oxford, researching Lollards and the Psalms.